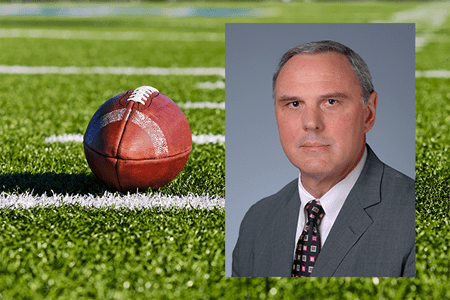

IU sports cardiologist leads cardiac screening for NFL Scouting Combine, urges everyone to learn hands-only CPR

A fascination with electricity is what led Richard Kovacs, MD, to a career in cardiology. While most people recognize the brain runs on electrical signals, so does the human heart.

That’s why quick treatment with cardiopulmonary resuscitation and an automated external defibrillator, or AED, is essential when a person experiences cardiac arrest. Defibrillators are designed to “shock” the heart back into normal rhythm. As a specialist in sports cardiology, Kovacs stresses the importance of having AEDs at all athletic fields and arenas.

“Have an emergency action plan that includes an automatic defibrillator at the competition site and proper training for coaches and trainers to operate the equipment,” said Kovacs, a primary investigator at the Krannert Cardiovascular Research Center and interim director for the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine at Indiana University School of Medicine who specializes in heart and vascular care for IU Health Physicians Cardiology.

“If it’s locked in the trainer’s office at the high school and the cross-country team is running two miles away, it does no good.”

“If it’s locked in the trainer’s office at the high school and the cross-country team is running two miles away, it does no good.”

The phenomenon of sudden cardiac arrest came into the public consciousness after basketball player Keyontae Johnson collapsed while playing a collegiate game for Florida State in 2020, followed closely by Danish soccer star Christian Eriksen collapsing on the field during the UEFA Tournament. In 2023, NFL football player Damar Hamlin suffered a sudden cardiac arrest after a blow to the chest. Later that year, collegiate basketball player Bronny James collapsed on the court from a previously unidentified congenital heart defect. All survived due to rapid treatment by team physicians using CPR and an AED.

Although these events are rare, it’s something Kovacs works with the NFL to help prevent through heart screenings for potential players. Every year for more than a decade, Kovacs has led cardiovascular evaluations for the NFL Scouting Combine, held annually in Indianapolis. A former collegiate football player for the University of Chicago, Kovacs enjoys interacting with rising athletes and NFL team physicians during the combine, running this year from Feb. 29 to March 3 at Lucas Oil Stadium.

The event, which is open to the public, is considered a “four-day interview” where more than 300 NFL hopefuls show off their skills. Kovacs’ job is to make sure their hearts aren’t harboring any potential timebombs. The risk of sudden cardiac arrest in the NFL is about 1 in 10,000, he said.

“We are looking for rare things,” Kovacs said. “Most of those athletes identified for further evaluation or treatment have gone on to participate in the draft and played in the league.”

Sports cardiologists use tools like electrocardiograms (EKGs) to detect cardiac arrhythmias and echocardiograms (cardiac ultrasound) to look for heart muscle and valve abnormalities. Sometimes advanced testing, such as cardiac MRI or a cardiopulmonary stress test is warranted. All tests are completed during the few days the athletes are in Indianapolis.

Sports cardiologists use tools like electrocardiograms (EKGs) to detect cardiac arrhythmias and echocardiograms (cardiac ultrasound) to look for heart muscle and valve abnormalities. Sometimes advanced testing, such as cardiac MRI or a cardiopulmonary stress test is warranted. All tests are completed during the few days the athletes are in Indianapolis.

The cardiology team is part of a larger group of IU Health physicians evaluating everything from joints to neurological systems.

“It’s like the world’s busiest clinic for three days for giant people,” said Kovacs, who stands at 6 feet but often feels small compared to the athletes.

It’s rare Kovacs needs to sideline a player — he’s not out to be a dream crusher.

“It’s a weird situation for players going through all these screenings,” Kovacs said. “They’re worried someone will say, ‘You can’t participate in the NFL,’ when that’s your life’s dream. Ninety-nine out of 100 times, I say everything’s fine. These athletes have trained for a decade or more to do what they really love to do.”

Physicians working at the combine understand the bodies of elite athletes. Because of their training regimens, they can have healthy hearts that appear enlarged or have thicker heart muscles than nonathletes.

“You need experts in sports cardiology who understand the sport, as well as how each position trains, to distinguish normal from abnormal,” Kovacs said. “A wide receiver’s heart doesn’t look like the offensive lineman’s heart, or the quarterback’s or the kicker’s.”

As founding chair of the sports cardiology section for the American College of Cardiology (ACC), Kovacs successfully advocated for legislation in Indiana that mandates high school coaches be certified in CPR. He also supports the NFL Smart Heart Sports Coalition, which advocates for every high school athletic venue to have an emergency action plan that is widely distributed and rehearsed, along with a clearly marked AED available within 1-3 minutes and coaches who are trained in both CPR and AED use.

Becoming a leader in cardiology

A first-generation physician, Kovacs worked his way through undergrad at the University of Chicago and then medical school at the University of Cincinnati as a researcher in sleep laboratories, examining brain electricity and neurophysiology. When his interest shifted to heart electricity, his search for top residency programs in cardiology led him to IU.

“There weren’t a lot of great cardiology programs at the time, and Indiana was the premier place,” Kovacs said.

Much credit for the program’s reputation goes to Charles Fisch, MD, Cardiology Division leader at IU School of Medicine from 1961 to 1990 and founding director of IU’s first heart clinic, predecessor to the Krannert Cardiovascular Research Center. Fisch became a key mentor for Kovacs, along with former Department of Medicine Chair August Watanabe, MD, who went on to become executive vice president of science and technology for Eli Lilly and Company. Kovacs briefly followed Watanabe to Lilly, steering his electrophysiological research toward drug development, but returned to IU School of Medicine in 2003.

“The theme here is mentorship,” Kovacs said. “I had tremendous mentors who offered me leadership opportunities.”

“The theme here is mentorship,” Kovacs said. “I had tremendous mentors who offered me leadership opportunities.”

When Kovacs started in cardiology in the 1980s, there were no subspecialities.

“Now with the complexity of technologies we can apply, we need to have experts,” he said. “Electrophysiology was the first subspecialty with the advent of defibrillators and pacemakers. Next came interventional cardiology to treat heart attacks acutely with stents and later to place heart valves.”

Along with electrophysiology and interventional cardiology, IU School of Medicine fellowship programs include Advanced Heart Failure and Transplant, Cardiovascular Disease, and Adult Congenital Heart Disease.

“Because of the outstanding work going on at Riley (Children’s Health), affected children are now surviving into adulthood at increasing rates,” Kovacs said. This means specialists are needed to care for patients with congenital heart diseases as they age.

In 2019, Kovacs was elected president of the American College of Cardiology, and he has held many other leadership positions within the national organization over the years.

“An important need in cardiology now is diversity and inclusivity,” Kovacs said. “Most of my mentors looked like me. Now I recognize that to care for patients, conduct better research and do clinical trials, those people (training cardiologists) should not all look like me.”

Julie Clary, MD, vice chair for clinical affairs in the Department of Medicine, is among several women Kovacs has informally mentored.

“As someone who was interested in leadership, advocacy and being involved with the American College of Cardiology, I couldn't think of anyone better to act as a coach,” said Clary, who joined the IU School of Medicine faculty in 2015 and serves as director of cardiac rehabilitation with IU Health. “It truly is an honor to work alongside Dr. Kovacs and learn from him each day. He is respected nationally and internationally, but he chooses to practice here at Indiana University — we are lucky to have him.”

“As someone who was interested in leadership, advocacy and being involved with the American College of Cardiology, I couldn't think of anyone better to act as a coach,” said Clary, who joined the IU School of Medicine faculty in 2015 and serves as director of cardiac rehabilitation with IU Health. “It truly is an honor to work alongside Dr. Kovacs and learn from him each day. He is respected nationally and internationally, but he chooses to practice here at Indiana University — we are lucky to have him.”

Roopa Rao, MD, an associate professor of clinical medicine who specializes in heart failure and transplants, considers Kovacs a source of invaluable career guidance, an inspiring expert in EKG and a role model for leadership.

“Rounding with him as a cardiology fellow in the hospital was an enjoyable experience, witnessing his adeptness in effortlessly solving challenging clinical cases,” she said. “I recall the strong attachment his patients had to him, demonstrating their unwavering trust and loyalty. It was remarkable to witness individuals willingly travel for hours just to continue their follow-up care under his guidance.”

A leader in cardiology “must be in the trenches” to maintain clinical credibility, Kovacs said, which is why he still sees patients most days.

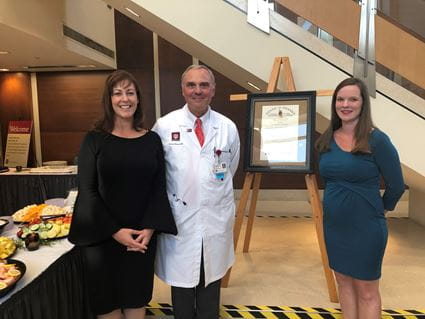

To recognize Kovacs’ service as president of the ACC in 2019, Clary successfully nominated him for Indiana’s highest civilian honor, the Sagamore of the Wabash. Presenting the prestigious award on behalf of Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb, Jennifer Sullivan, MD, MPH, then-secretary of the Indiana Family and Social Services Administration, noted Kovacs’ “magical powers to know where he is needed at exactly the right time.”

She was referencing a 2019 incident when an IU School of Medicine faculty member collapsed from sudden cardiac arrest while running in Paris. Amazingly, Kovacs was also in Paris for a cardiology conference and was able to attend to the faculty member in the hospital. He later served as a medical escort on the flight home.

An important part of the story, Kovacs said, is that another runner quickly intervened to perform lifesaving CPR while waiting for paramedics to arrive. Unfortunately, the U.S. lags behind Europe in public training for cardiac emergencies, he noted.

Saving lives with CPR and AEDs

Here's a sobering statistic Kovacs often shares: “If you collapse on the street in Prague, there is a 98% chance a bystander will start CPR. If you collapse in Indianapolis, there is about a 10% chance.”

Here's a sobering statistic Kovacs often shares: “If you collapse on the street in Prague, there is a 98% chance a bystander will start CPR. If you collapse in Indianapolis, there is about a 10% chance.”

More than 356,000 people have out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in the U.S. every year, and nearly 90% of them are fatal, according to the American Heart Association Heart and Stroke Statistics—2023 Update. Most of these events occur in homes and public settings. Intervening with CPR immediately can double or triple a person’s chance of survival, according to the AHA.

The American Red Cross website has step-by-step instructions and video tutorials for adult CPR, hands-only CPR, child and baby CPR, and pet CPR. The Red Cross also offers online and in-person CPR classes which include instructions for using an AED. There are even stations at the Indianapolis International Airport where anyone can practice CPR on a manikin, Kovacs noted.

As much as he enjoys working with athletic organizations like the NFL, Kovacs stresses that the odds of an athlete having a sudden cardiac arrest on the field are low compared to the probability of encountering cardiac arrest in everyday life.

His message for American Heart Month is this: “Lives would be saved if people learned hands-only CPR and were comfortable with using an AED.”