“Of all the nonprofits, they chose to highlight the Barth Syndrome Foundation,” Allen recalled. “When I saw the family they featured, I thought, ‘Oh my gosh! That looks like Henry!’”

Allen had spent countless hours researching her son’s symptoms and had even come across studies on Barth syndrome, but Henry’s early doctors thought he likely had another condition due to the syndrome’s rarity. Fewer than 400 estimated people worldwide, predominately males, are currently diagnosed. Still, Allen couldn’t shake the feeling that a genetic disorder was behind his health struggles, which included heart issues, abnormal mitochondrial test results and slow growth.

Barth syndrome affects the cardiovascular and immune systems, leading to heart problems, muscle weakness and developmental delays. Another common symptom is frequent infections due to neutropenia, a condition characterized by abnormally low white blood cell counts. In early 2010, Henry was admitted to Riley Hospital for Children, where doctors discovered he had neutropenia.

“His neutrophil count went down to zero, which is super rare,” Allen said. “They thought maybe he had leukemia or another type of cancer, but when Henry’s pediatric hematologist-oncologist, Grzegorz Nalepa, came into the room and mentioned neutropenia, I immediately thought of Barth syndrome.”

That moment reignited Allen’s memory of the “Today” show segment and all the research she had done at home. She recalled neutropenia being mentioned as a symptom and urged Grzegorz Nalepa, MD, to run genetic tests. The results confirmed what she had long suspected — Henry had Barth syndrome.

Diagnosis to discovery

Shortly after her son’s diagnosis, Allen learned that Nalepa wasn’t just a doctor at Riley Children’s Health, he was also a physician scientist at the Indiana University School of Medicine. They both recognized the immense value of advancing Barth syndrome research locally at a leading academic medical institution, where cutting-edge discoveries could translate into real-world impact. This shared vision marked the beginning of a transformative collaboration.

Early on, Nalepa discussed the possibility of using a mouse model with Henry’s specific genetic mutation.

“This mouse would help all kids, not just Henry,” Allen said. “It wouldn’t just help Barth syndrome research; it could also contribute to studies on Parkinson’s, diabetes and Alzheimer’s. I thought, ‘We won't know until we try.’ Even if the research fails, it’s worthwhile because we learn what won’t work.”

By sequencing Henry’s DNA, they successfully identified the mutated gene responsible for his condition. The team then replicated this mutation in a mouse, hoping to create a model that would allow researchers to study Barth syndrome in an entirely new way.

As the project took shape, Nalepa connected with his colleague at the Herman B Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Simon Conway, PhD. Conway is a developmental biologist focused on studying birth defects and the cardiovascular system, making him an ideal collaborator for this groundbreaking work.

“The goal was to characterize this mouse model to see if it's a good fit for what’s seen in patients,” said Conway, a professor of pediatrics at the IU School of Medicine. “We were able to compare Henry’s phenotypes with what we saw in the mouse, and they were a good match.”

Because Barth syndrome is rare and life-threatening — most patients eventually require heart transplants — the successful development of the patient-derived mouse model is a major advancement for future research and finding a cure. The model enables scientists to study the disease’s influence on neutrophils, skeletal muscles and the heart in ways that previously seemed impossible.

“It's very difficult to study a syndrome and a disease when there are so few surviving patients,” Conway explained. “Plus, you don’t want to give them any more stress than they already have, so researchers have developed ways to get around that. But in terms of trying to study the heart as a functioning, living organ, our patient-derived mouse model is the best genetic option we have available. It’s a critical stepping stone to developing or identifying potential therapies.”

“It's very difficult to study a syndrome and a disease when there are so few surviving patients,” Conway explained. “Plus, you don’t want to give them any more stress than they already have, so researchers have developed ways to get around that. But in terms of trying to study the heart as a functioning, living organ, our patient-derived mouse model is the best genetic option we have available. It’s a critical stepping stone to developing or identifying potential therapies.”

Nalepa led this groundbreaking research until his unexpected passing in 2018. Highly respected in his field, he left behind a lasting legacy that Conway and Allen were determined to continue.

“I wasn't sure if the research would continue or not,” Allen said. “When Simon took over as lead investigator, we felt very fortunate because the whole experience could have ended.”

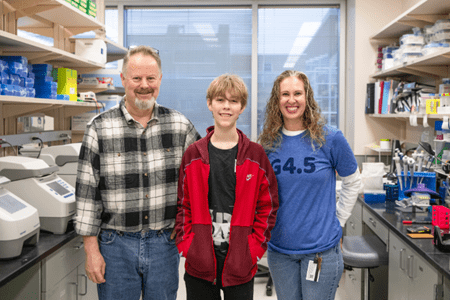

Since taking over what Henry calls “Henry’s mice,” Conway and his colleague Paige Snider, PhD, have continued advancing the research. They have published several studies, and Conway even led a presentation about their patient-derived model at the Barth Syndrome Foundation’s International Scientific, Medical and Family Conference in 2024. The biennial event brings affected families, research scientists and clinicians together to advance research and advocacy efforts.

With a solid understanding of the disease’s cardiovascular effects, the team’s future research will focus on skeletal muscle function and other underlying causes of the disorder. On a wider scale, Conway believes their work may provide valuable insights into other conditions that share similarities with Barth syndrome.

Making a difference

From the start of her journey with Nalepa and Conway, Allen knew the scientific research would require significant resources. She took the lead in organizing annual fundraising events with the help of her friends, family and the Riley Children’s Foundation. For nearly a decade, they have hosted a variety of fundraisers, including bowling events, Chicago Cubs games and a pet calendar photo contest. These efforts have raised almost $200,000 for Barth syndrome and congenital heart disorder research at the Wells Center.

“They helped Grzegorz’s research, and now they’re helping ours,” Conway shared. “It’s their way of giving back to us, but ultimately, it supports our way of giving back to them.”

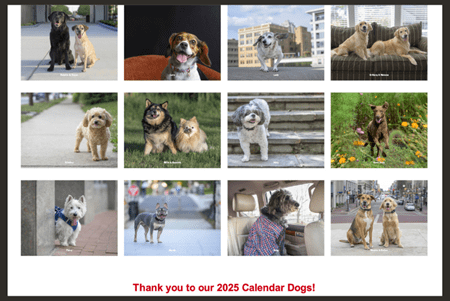

The Dogs for Riley Pet Photo Contest began after the COVID-19 pandemic made in-person events more challenging, and it was a natural fit as Allen is a professional photographer. Each year, pet lovers submit photos of their dogs to enter the contest. Donations are required to enter and vote, with proceeds benefitting the Riley Children’s Foundation and the Conway lab. At the end of the contest, the pets with the most votes are crowned winners and have their photos professionally taken by Allen in Indianapolis. The images are then used to create a calendar, which is sold at the end of the year to further support the Conway lab’s research.

“It's very, very competitive to become a dog of the month,” Conway admitted.

As for Henry, he is managing his condition well and enjoying life as a high school student. Allen hopes that one day there will be a cure for Barth syndrome, and she believes that innovative research, along with community support, will make all the difference. She encourages other families coping with rare disease diagnoses to stay positive and do what they can to make an impact.

As for Henry, he is managing his condition well and enjoying life as a high school student. Allen hopes that one day there will be a cure for Barth syndrome, and she believes that innovative research, along with community support, will make all the difference. She encourages other families coping with rare disease diagnoses to stay positive and do what they can to make an impact.

“My advice to someone who finds out their child has a rare disease, or any disease, is to connect with an organization involved with that condition,” Allen said. “I’m not a doctor or a scientist, but the thing I could try to do was fundraise. We all have the power to help.”

To learn more about the Dogs for Riley Pet Photo Contest, visit the contest website. The 2025 contest runs from February 14 to March 1, with final 2026 calendars available to the public in late November or early December 2025.