IU’s Undiagnosed Rare Disease Clinic gains national distinction for expertise in diagnosing unknown genetic disorders

From her first day of life, Aly Edmondson struggled with feeding. By 12 months, she weighed just 14 pounds and was diagnosed with “failure to thrive.” For the next 15 years of her life, she would be in and out of hospitals and doctor’s offices with a slew of symptoms — cataracts, mouth sores, esophageal inflammation, hair loss, skin rashes — all seemingly unrelated. Her family and even her doctors would say she had “Aly syndrome.”

Turns out, they were spot on. After a 16-year diagnostic odyssey, Aly finally has an answer for her string of medical maladies — a genetic disorder so rare it doesn’t have a name.

Credit goes to the scientific sleuths at the Undiagnosed Rare Disease Clinic (URDC) at Indiana University School of Medicine for uncovering the diagnosis tying all her mysterious symptoms together.

Aly’s mother, Melissa Edmondson, struggled to find words to describe the moment of diagnosis: “excitement, disbelief, relief — shock maybe.”

“I almost couldn't believe that what had been random diagnoses with no apparent logic since she was a baby were now linked,” Melissa said.

Aly is among 25 million to 30 million Americans living with rare diseases, defined as disorders affecting fewer than 200,000 people. Collectively, that’s nearly 10% of the U.S. population — about four people on every bus — according to the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD). In Aly’s case, there are only nine known patients worldwide with the same disorder caused by a mutation of the MBTPS1 gene, which affects mitochondrial function and cellular stress response.

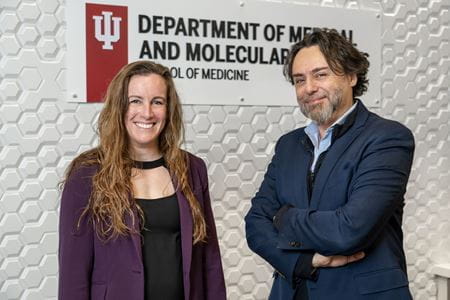

“We deal mostly with ultra-rare diseases,” said Francesco Vetrini, PhD, MSc, a clinical molecular geneticist who co-directs the rare disease clinic with Erin Conboy, MD. “In many cases, the gene is not discovered yet.”

“We deal mostly with ultra-rare diseases,” said Francesco Vetrini, PhD, MSc, a clinical molecular geneticist who co-directs the rare disease clinic with Erin Conboy, MD. “In many cases, the gene is not discovered yet.”

The URDC uses the most advanced genomic testing, scours medical literature, and networks with physicians and scientists throughout the world to investigate the cold cases of genetic intrigue. It can take years to find the “smoking gun” hiding among an individual’s 20,000-25,000 genes.

The clinic sees patients at Riley Hospital for Children with genetic investigation conducted by researchers in the IU School of Medicine Department of Medical and Molecular Genetics. The URDC at IU is among just 40 such clinics nationwide — and the only one in the region — to be named a NORD Rare Disease Center of Excellence.

“These centers are places families can trust to have expertise in rare disease,” Conboy said. “IU is filling a large gap of need in the Midwest region.”

Last year, the URDC joined a short list of institutions comprising the NIH-funded Undiagnosed Diseases Network, which includes powerhouse medical research centers like Boston Children’s Hospital, Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and Seattle Children’s Hospital (University of Washington School of Medicine).

“We were kind of isolated before,” Vetrini said. “Now we are part of this incredible collaborative network and can leverage resources to help us solve these difficult cases.”

The genetics of a unicorn

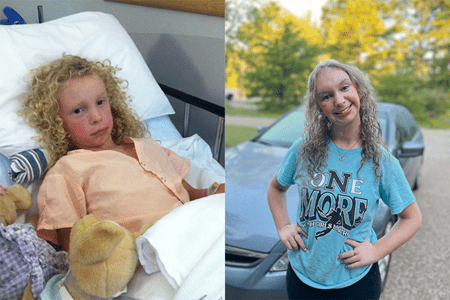

In the medical community, rare conditions are known as zebras — something with hoofbeats like a horse but much more exotic. In Londyn Hoffman’s case, she’s more like a unicorn. Not only does she have an unnamed genetic disease, but she’s also survived a rare cancer, Rhabdomyosarcoma. Then, she was diagnosed with Guillain-Barre syndrome, a rare disorder which caused her body’s immune system to attack her nerves.

In the medical community, rare conditions are known as zebras — something with hoofbeats like a horse but much more exotic. In Londyn Hoffman’s case, she’s more like a unicorn. Not only does she have an unnamed genetic disease, but she’s also survived a rare cancer, Rhabdomyosarcoma. Then, she was diagnosed with Guillain-Barre syndrome, a rare disorder which caused her body’s immune system to attack her nerves.

“What makes her even more like a unicorn is her ability to shine through all of these diagnoses, hospital stays, chemo treatments, pokes and prods — leaving sparkle everywhere she goes,” said her mom, Jenna Hoffman.

Londyn started down the path of genetic testing before her first birthday. She was failing to hit developmental milestones.

Vetrini and Conboy are part of an international team that finally cracked this case, discovering a new gene in the process. Their findings, published in Human Molecular Genetics, describe a variation in the protein-coding gene RAB5C that leads to macrocephaly (large head) and developmental delays. Londyn is one of just 12 known cases in the world.

“This was a multicenter and multidisciplinary collaboration,” Vetrini said. The study included cases and researchers from across the globe — the Netherlands, Canada, Poland, France, Germany and Australia. “Who knows how many other patients may have changes in this gene, and now they can benefit from the information that we provide.”

While all individuals in the study have developmental delays, Londyn is the only one who had a cancerous tumor. While undergoing chemotherapy and radiation, she also experienced weakness in her breathing muscles, leading to the Guillain-Barre diagnosis.

Londyn ultimately had her eye removed after a second bout of cancer, but she is now cancer-free and spreading cheer to her teachers and friends at school and anyone she encounters at her big brother’s baseball games. She even plays on a Miracle League baseball team.

“At this point, we firmly believe anything is possible with Londyn,” Jenna said. “It may take her a little longer to reach each (developmental) goal, but eventually, she does it and astonishes us all. As we say, she does everything on ‘Londyn time.’”

“At this point, we firmly believe anything is possible with Londyn,” Jenna said. “It may take her a little longer to reach each (developmental) goal, but eventually, she does it and astonishes us all. As we say, she does everything on ‘Londyn time.’”

Vetrini has developed a working theory on how Londyn’s genetic variant could have contributed to her rare sarcoma. Other congenital genetic conditions are known to predispose to cancer, Conboy said.

There is still a lot to learn about the RAB5C gene, and Londyn is among those who will help researchers develop a prognosis for those affected with this disorder. There is now a community of unicorns.

“Dr. Conboy and the URDC team do a great job of educating us on genetics — the ‘why’ behind our unicorn,” Jenna said. “While Londyn is still a giant medical mystery, we are grateful for the team’s support in navigating unknown terrain every step of the way.”

‘We never give up.’

In Aly’s case, the URDC team collaborated to discover and describe an emerging novel syndrome.

Aly first had whole exome testing done in 2018, but the affected gene it identified had no known diseases associated with it, making diagnosis impossible at the time, Conboy said. The URDC kept digging for other cases and found a few related to the same genetic mutation, but the symptoms didn’t match. It wasn’t until the URDC team came across a case published by medical scientists in China in 2022 that they knew they had the smoking gun — something the Chinese research team described as “cataract, alopecia, oral mucosal disorder and psoriasis-like syndrome,” or CAOP.

Aly first had whole exome testing done in 2018, but the affected gene it identified had no known diseases associated with it, making diagnosis impossible at the time, Conboy said. The URDC kept digging for other cases and found a few related to the same genetic mutation, but the symptoms didn’t match. It wasn’t until the URDC team came across a case published by medical scientists in China in 2022 that they knew they had the smoking gun — something the Chinese research team described as “cataract, alopecia, oral mucosal disorder and psoriasis-like syndrome,” or CAOP.

“Once a patient enrolls in our program, we never give up,” Vetrini said. “We keep looking at the literature and how the knowledge of the gene evolves over time.”

Surprisingly, the team uncovered a simple treatment to help with Aly’s skin symptoms: riboflavin (vitamin B2).

“Her hair has started to grow back, and her skin condition improved,” Conboy said.

Although Aly still deals with many symptoms of her medical condition, she is also a typical 16-year-old girl who just started driving, enjoys shopping and dancing, and identifies as a “Swiftie.” Aly and her mom traveled to Nashville for the Taylor Swift Eras Tour last May.

Melissa calls the URDC team “an answer to a whole lot of prayers.”

Because rare diseases, by definition, affect a small percentage of the population, funding is a challenge. Families referred to the URDC pay nothing for the team’s genetic sleuthing, which often spans years. To help support this important research, Riley Children’s Foundation has established a special fund for the Undiagnosed Rare Disease Clinic.

“I think they’re amazing,” Melissa said. “After all this time, for them to not give up on Aly — to follow up and keep going and finally have the answer to the mystery of 16 years — it really means a lot.”