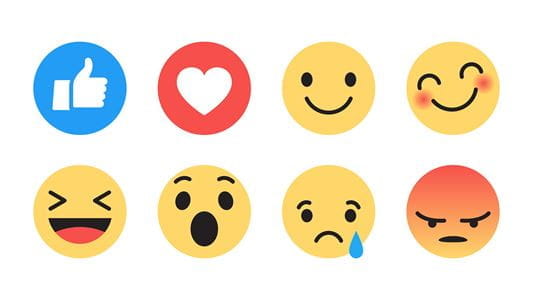

You may have heard it said before that a picture is worth a thousand words, but what about an emoji?

Since emoji were first created in the 1990s, their use has evolved and increased significantly in text messaging, social media, email and more. And now, even clinicians are using them when communicating with each other at work.

“It's very interesting, the idea that a single emoji has some kind of meaning, but could mean something different to different people,” said Colin Halverson, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at Indiana University School of Medicine.

Halverson, along with Mike Weiner, MD, MPH, Claire Donnelly, MA, and senior author Joy L. Lee, PhD, MS, recently published a study in JAMA Network Open about emoji use among hospitalists using the Diagnotes messaging app at Indiana University Health. The researchers looked through thousands of lines of messages to find anything with an emoji, then analyzed the emoji use to determine what roles they played in the messages.

“We wanted to determine whether they were just being what we call duplicative, meaning they just duplicated information that already existed, or if they actually performed a linguistic role that might be meaningful and separate from the alphanumeric text,” Halverson said. “For example, is using a thumbs up really adding new information, or just being used in a way that doesn’t add anything new, and could that be considered distracting and annoying to clinicians? Does that impact workflow in some way?”

“We wanted to determine whether they were just being what we call duplicative, meaning they just duplicated information that already existed, or if they actually performed a linguistic role that might be meaningful and separate from the alphanumeric text,” Halverson said. “For example, is using a thumbs up really adding new information, or just being used in a way that doesn’t add anything new, and could that be considered distracting and annoying to clinicians? Does that impact workflow in some way?”

A linguistic anthropologist, Halverson has a background in linguistics and ethics. Some of his past research work includes studying emoji and skin-tone modifiers as well as the different meanings different people associate with emoji. Halverson said while many studies about emoji exist, they are mostly focused on informatic approaches to analysis. And until now, emoji use among clinicians has never been studied empirically.

“We did not find any confusion arising from emoji use and we did not find any implications that there’s a concern about professionalism with the emoji that were used,” Halverson said. “Obviously, you can use emoji just like any other form of language in ways that are inappropriate, but it doesn’t seem like emoji are any more prone to that than words.”

For this study, 80 hospitalists were included. Halverson said future studies could look closer at generational differences in emoji use and emoji use in different clinical texting systems, in addition to expanding the number of and types of clinicians and messages analyzed.

“This article represents significant work on how clinicians communicate with each other as technology evolves, which will be more and more important to understand as time goes on,” Halverson said. “No one has done this yet in the area of health care, so there are a lot more questions to ask.”

Read the full publication in JAMA Network Open.